Time

Discover 20 key dates that capture more than 150 years of Richmond’s unique history at the mouth of the Fraser River.

let’s go!

First

Peoples

Indigenous Peoples arrive in the region at the end of the Ice Age and thousands of years before today’s city was born.

Over time, the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ speaking peoples witness changes to the shape of the islands and the river’s path to the Salish Sea. They paddle waterways between islands rich in grass and clusters of spruce and harvest roots and berries, fish for salmon and sturgeon, and hunt deer, muskrats, beavers, seals and sea lions with the seasons.

The hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ speaking peoples’ deep connections to this region remain to this day.

New Arrivals

Hugh McRoberts is the first of a slow but steady stream of farmers to Lulu and Sea Islands. In 1859, Joseph Trutch and the Royal Engineers survey the islands now known as Richmond, dividing them into 160-acre blocks, which are made available to homesteaders.

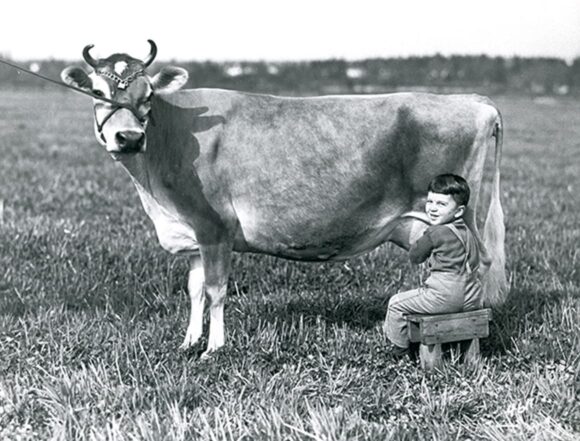

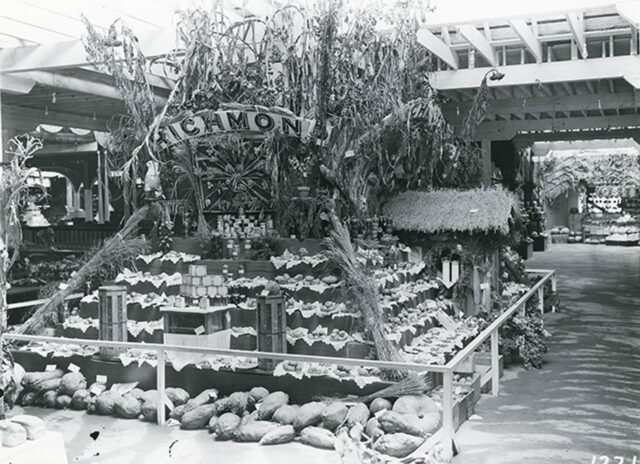

Richmond’s islands soon becomes the Lower Mainland’s “breadbasket,” supplying nearby cities with vegetables, grains, dairy and beef.The homesteaders are joined as early as 1883 by Chinese labourers, who work digging drainage ditches and building roads. Five years later, Gihei Kuno arrives from Japan and quickly spreads stories of a river dancing with salmon to other fishermen in his hometown of Mio. They soon follow him here. The multiethnic city we know today starts to take root.

A Town

is Born

The settlers’ goal is to create a local government that can levy taxes to develop and maintain dikes, roads, bridges and other services. They are successful and the Township of Richmond is established in 1879.

The network of dikes started by the municipality has kept Lulu and Sea Islands safe from high tides, spring run offs and storms to this day – even during the floods of 1894, 1948, 1972 and 2021. There are a few small-scale exceptions including some areas of Mitchell Island, which flood in 1948 before dikes are built there.

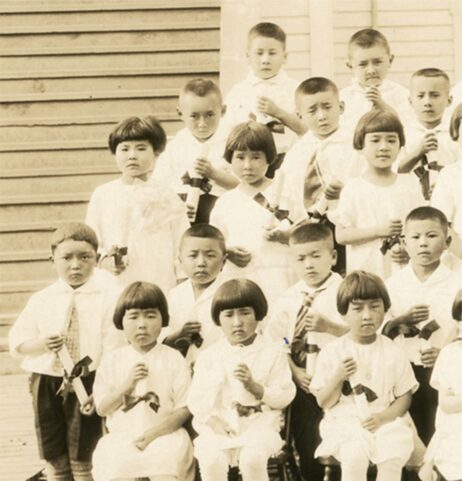

Building Schools

Mr. Robertson is the first teacher in Richmond’s first purpose-built, one-room school at No. 2 Road and Steveston Highway.

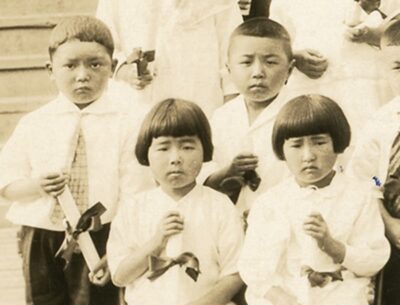

Schools continue to open to meet the demands of the rapidly growing number of families in Richmond.In 1909, Steveston’s Japanese community raises funds to open their own school as their children are not allowed to attend schools run by the School Board. In 1923, it takes responsibility for all children in Richmond. Lord Byng becomes the first and only school in BC to hire a Japanese Canadian teacher, Miss Hide Hyodo, who is permitted to teach only Japanese students.

The end of World War II creates another period of tremendous growth. As land is developed, areas are set aside for parks, schools and accompanying sports fields – a pattern we can still see in our city today.

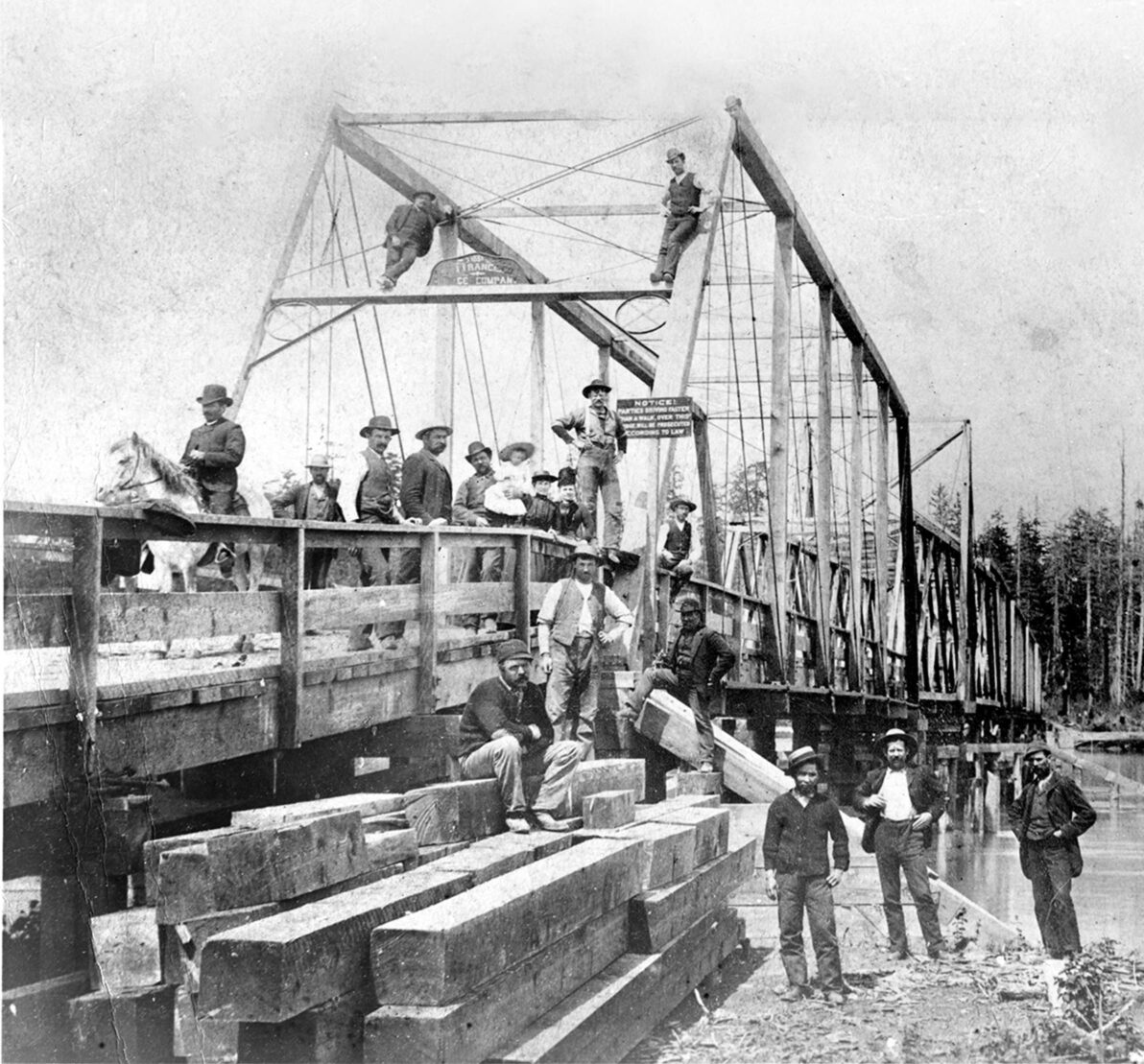

Building Bridges

The North Arm Bridge at Eburne opens to horse-drawn traffic in 1889, only to be destroyed by ice floes that winter. The bridge is rebuilt the following year with a “swing span” that moves to allow boat traffic on the river to pass through. It also causes road traffic jams for most of the bridge’s life. The North Arm Bridge is finally dismantled in the 1950s and replaced by the Arthur Laing Bridge in 1975.

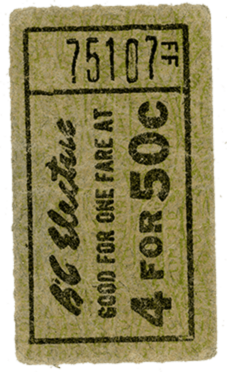

Trams and

Electricity

The “Sockeye Special” is created to serve Steveston’s canneries, but they prefer to load their cans of fish directly onto ships bound for overseas markets.

The BC Electric Railway Company subsequently leases the line in 1905 and aims at a new market, the public. The electricity powering its trams also brings supplies to the community of Steveston, as a bonus. Tram passengers pay 85 cents for a return Steveston- Vancouver trip. A one-way journey takes one hour and 15 minutes, including stops at 18 stations along the 13 km Lulu line. The Interurban Tram runs until 1958, when buses and cars take over.

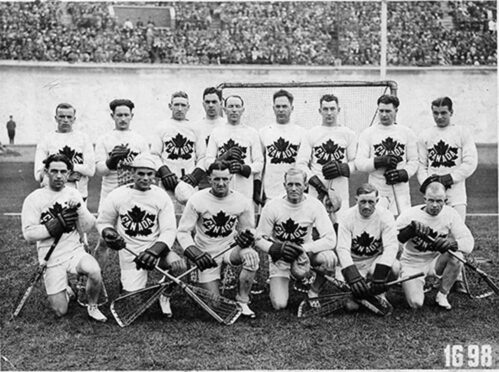

Competitive Sports

The Lansdowne Park Racetrack opens 15 years later, adding to the excitement. People from around the Lower Mainland arrive by the thousands on “Specials,” or Interurban trams especially scheduled to bring spectators to the races.

Other sports are popular too. Lacrosse is highly competitive and attracts large crowds. Later, in the 1960s and ‘70s, a fierce rivalry rages between the Richmond Colts and Steveston Packers high school volleyball, basketball and football teams. Fans and participants still vividly recall the games. The Kajaks Track and Field Club brings glory to the local sports community when they send their first athlete to the Olympics in 1968.

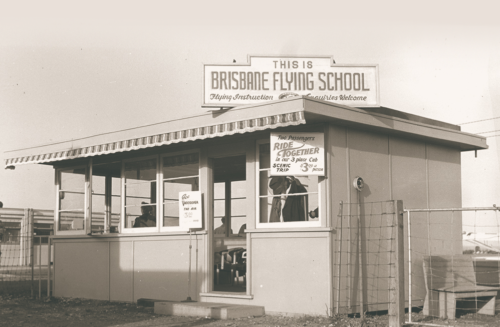

Taking Flight

Many flying firsts follow and lead to the opening of the Vancouver Civic Airport two decades later. It begins as a small development in a rural landscape, but soon expands to occupy most of Richmond’s Sea Island.

The Vancouver International Airport, located farther east, opens in 1948 and the Civic Airport becomes the South Terminal. Today’s Main Terminal opens in 1968. The Airport Authority signed a 30-year agreement with the Musqueam Nation in 2017 to protect important cultural sites, share profits, and create jobs. It’s no surprise that in recent years, the airport has been consistently recognized as one of the world’s best.

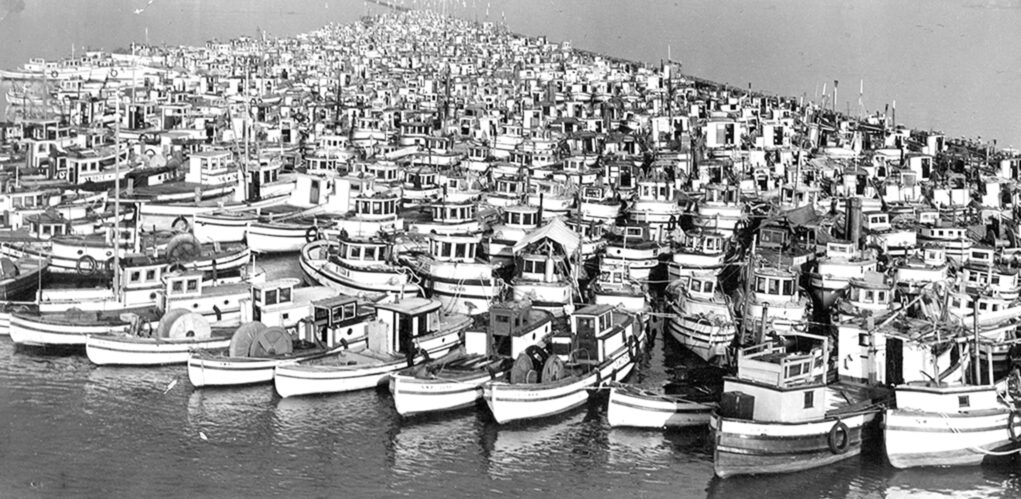

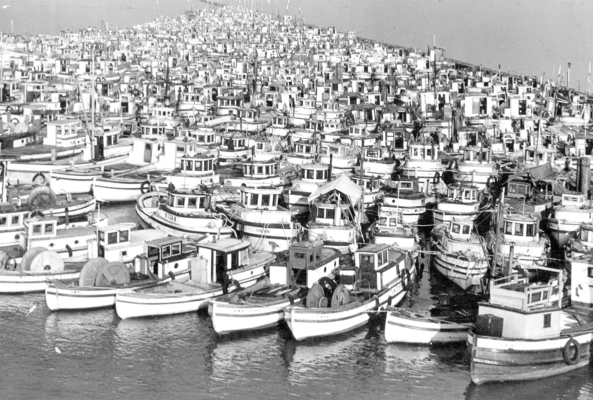

A Thriving Fishing Industry

Steveston, or “Salmonopolis,” bursts to life with each new fishing season as Indigenous, Chinese, Indo-Canadian and white workers flood into town for seasonal work in the canneries, while Japanese fishermen and boat builders live in the village year round. At the fishery’s peak, canneries run full throttle shipping canned salmon around the globe. In 1913, the largest sockeye run ever recorded yields more than 2.5 million cans of salmon.

Good Times

and Bad

If this were not enough, soldiers returning home after the end of World War I carry the Spanish Influenza, and death, with them. More hardships follow including the Great Depression, World War II, floods and declining fisheries.

But there are also good times. The community celebrates with Salmon Festival parades, maritime festivals, judo and bushido sporting events, opera and theatre performances, and builds schools, community centres, temples and churches.

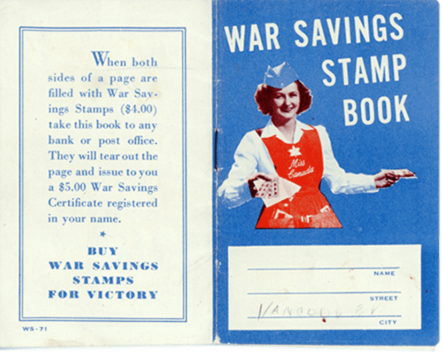

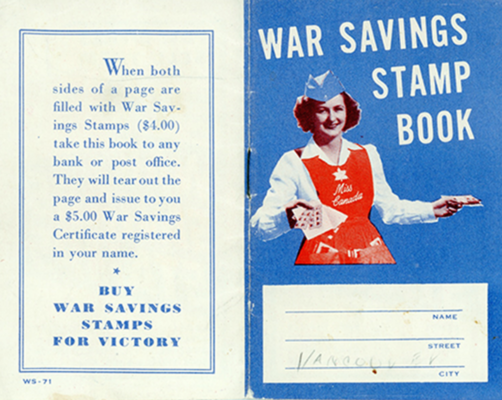

World War II

With more than 80 percent of its population gone, stores close and schools are emptied. Japanese Canadian belongings, including 1,200 fishing boats, are impounded and sold at rock bottom prices. The community is only permitted to return to the West Coast in 1949, four years after the war’s end.

On Sea Island, Burkeville is built to house workers making planes for the war effort. At its peak in 1945, the nearby Boeing Canada Aircraft plant has 7,000 employees. Many are women who go to work when the men leave to fight.

Connecting

to the World

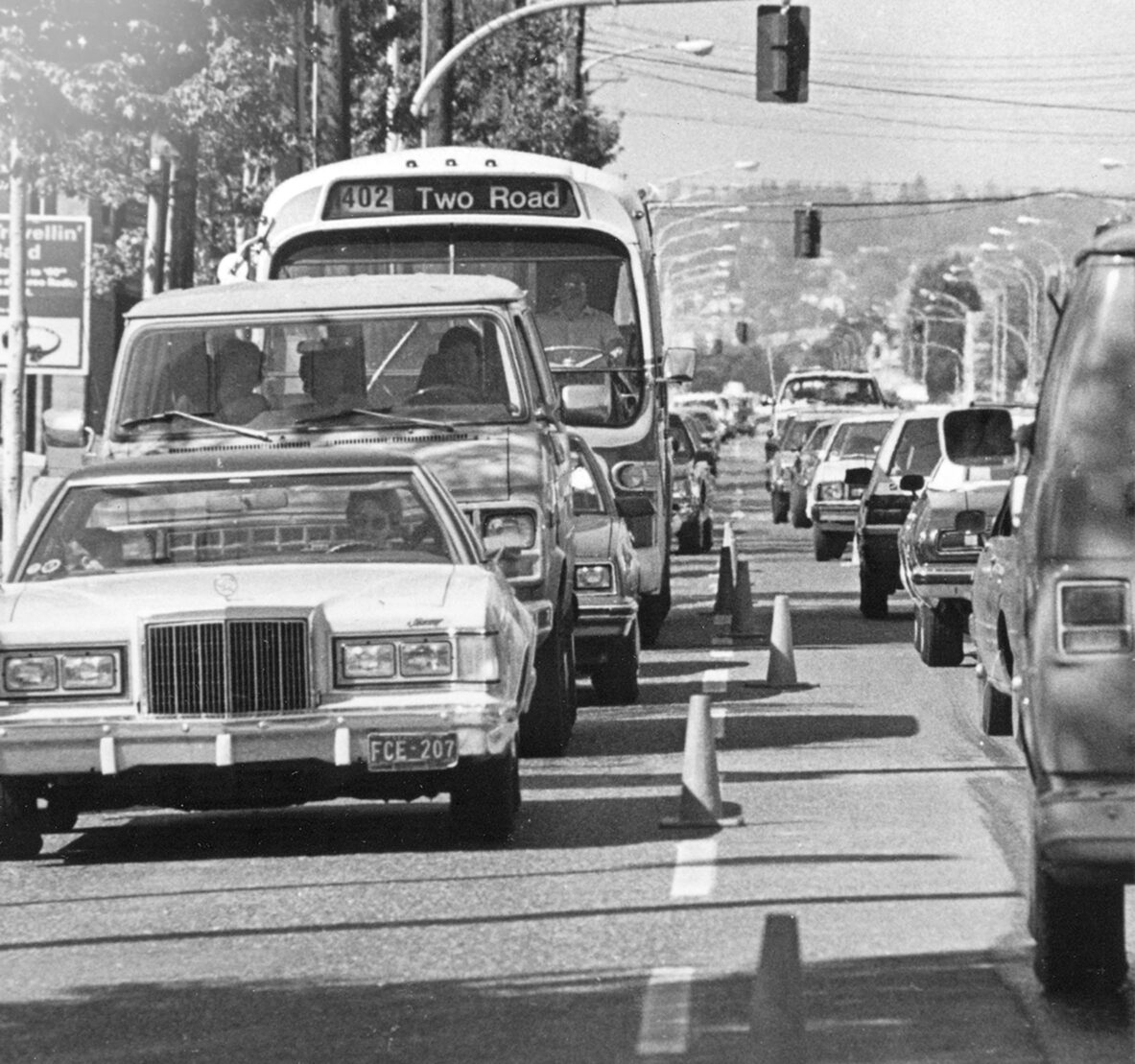

Richmond attracts new businesses and residents in the 1960s. To support this growth, new roads, bridges and tunnels are built including the Oak Street Bridge in 1957, the Deas Island (Massey) Tunnel in 1959 and the Knight Street Bridge in 1974. The Vancouver International Airport continues to grow and expands into the jet age.

These new transportation networks create stronger connections to jobs and markets in the Lower Mainland, the United States, and the world.The new roadworks end the era of Interurban trams and usher in the era of buses and automobiles. But commuting via rail returns to Richmond almost 50 years later.

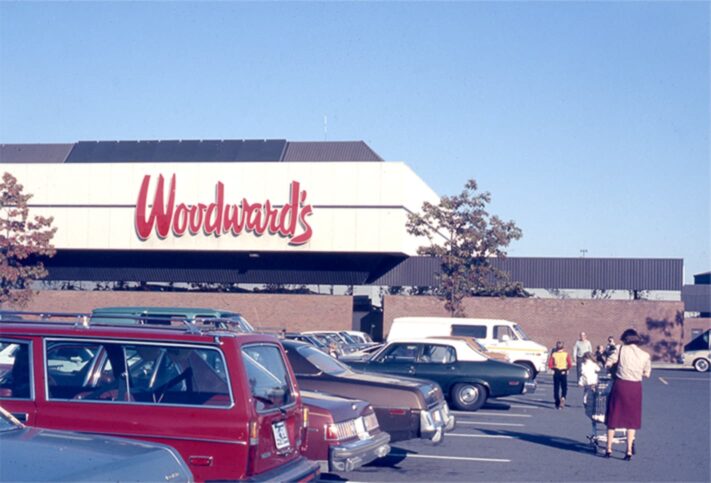

Big Chains Open Shop

The original “heritage” arches are restored and reinstalled when this McDonald’s restaurant is rebuilt 50 years later in 2017. Red and white tiles from the original restaurant are also preserved and set in concrete near the sidewalk, along with a commemorative plaque. Check it out!

Global restaurant chains and stores provide more choice for consumers, but spell the end of an era for many local businesses. Most family owned corner stores close and even the legendary Hong Wo General Store could not compete, shutting its doors for the last time in 1971 after serving the community for 76 years.

Creating a

Green Future

Close to 200 farms operate on the 39 percent of city permanently zoned for agricultural use. Blueberry and cranberry crops dominate, thriving in the peaty soil of central and eastern Lulu Island.

At the same time, other areas of the city are zoned for parks and different types of development, ensuring Richmond also remains safe and livable. The Richmond Nature Park is created to preserve the raised peat bog habitat that once covered large portions of Lulu Island and provides habitat for more than 100 species of resident and migratory birds, at least 13 species of mammals, ranging from tiny shrews to black-tailed deer, as well as garter snakes, frogs and many bugs.

Citizens

Make Change

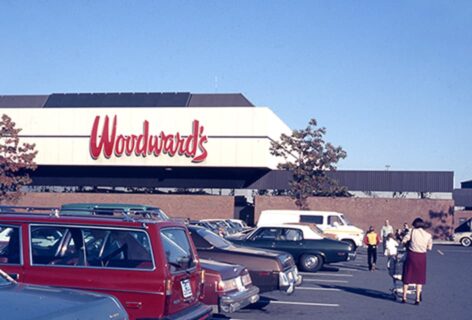

During a public meeting in 1973 she says, “The women of Richmond want Woodward’s. We want $1.49 Day,” and follows up with a petition containing more than 10,000 signatures. The issue is settled in the next municipal election with an overwhelming “yes” vote for the development of the Lansdowne Shopping Mall, including a Woodward’s store.

Elsewhere, citizens take action fighting against the development of Terra Nova. The battle results in the creation of a 100 acre park that preserves the unique rural character of the area.

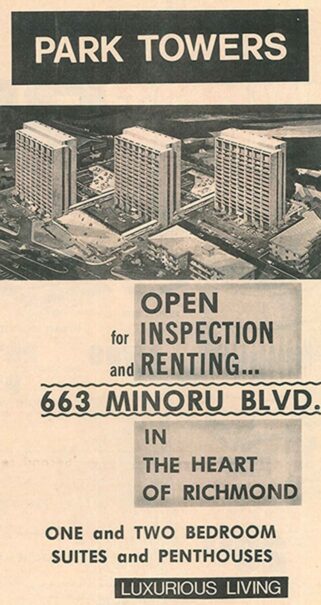

City centre begins to take its current form with the opening of the Richmond Shopping Centre in 1965 and the Richmond Hospital one year later. Nearby, Park Towers, Richmond’s first high rises open in 1971, changing the city’s skyline.

Growing Diversity

Richmond has been attracting people from around the globe since settlers began arriving from Europe, Japan and China close to 150 years ago. While settlers of European descent dominated in the city’s early years, more recently arrivals from Asia have become the majority.

In the 1990s, immigration from Hong Kong grew. Migration from China, the Philippines, India and other Asian countries accelerated in the following decades.Today, Richmond is a minority majority city with more than 75% of people identifying as a visible minority—the highest proportion of any municipality in BC and the second highest in Canada. Richmond residents include close to 150 ethnic groups, adding to the richness of our city. This cultural diversity makes Richmond an exciting place to live and visit.

Highway

to Heaven

In 1990, the area is rezoned for “assembly use” allowing religious facilities to be built on the front portions of agricultural land.

The Gurdwara Nanak Niwas is the first religious institution to welcome its community and is soon followed by the Ling Yen Mountain Temple and many others.

Today, Buddhist, Sikh, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim and Christian places of worship and schools are peacefully located side by side. One popular act of inter-faith cooperation is the sharing of parking on different days of worship.

Evolving Industries

The fishing industry, once the mainstay of Steveston, declines with fewer salmon, shortened fishing seasons and a reduced fleet. The Imperial Cannery is the last to close its doors in 1992.

Other industries grow. An average of 50 film and television productions are shot in the city every year and while Richmond prides itself in its livability, it also boasts close to 100,000 jobs in hi-tech, tourism, airport services and aviation, agriculture, fishing services, light manufacturing, retail and government.

Going for Gold

In 2009, the Canada Line opens connecting Richmond with Vancouver via rapid transit for the first time since 1958 and, as planned, one year ahead of the 2010 Winter Olympic Games.

Richmond hosts fiercely contested long-track speed skating events in the newly constructed Richmond Olympic Oval. While new records are being set at the rink, more than 1,000 volunteers join community partners to share the best of the city and provide unrivalled hospitality to Olympians and visitors. The Richmond O Zone comes alive with non-stop celebrations of our cultural heritage.

The Olympic legacy lives on with premier sporting facilities for locals, training facilities for performance athletes and national teams, and a boost in tourism.

Tackling

Climate Change

The first successful flight of an all-electric commercial aircraft is piloted by local company Harbour Air and partners, with the goal of making air travel greener, with fewer carbon emissions.

Earthbound plans to reduce our carbon footprint include the Lulu Island Energy Company’s use of geothermal energy and air-source pumps for heating and cooling more than 4,500 residential units in Richmond. The company, owned by the City of Richmond, has won 18 awards to date for its leading role in the development of low carbon district energy systems.

The City is also implementing a new flood protection strategy to reduce the effects of climate change, which includes raising the dikes to 4.7 metres above sea level.Other plans include fostering great urban spaces, island shorelines, open spaces and agricultural lands. Richmond is poised for its future role at the edge of the Pacific.