oral histories

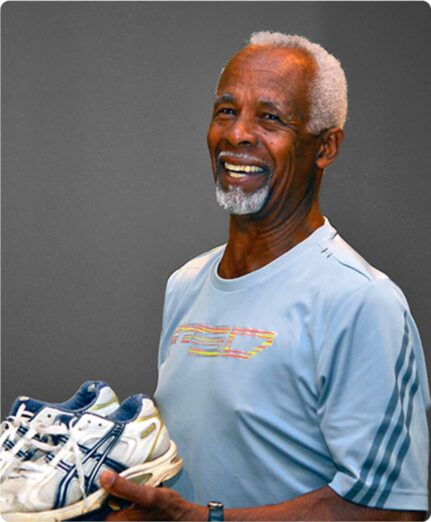

Moseley Jack

Things have worked out very, very well for me. This country has done amazing things for me.

Moseley Jack is a retired teacher, counselor, and coach. Born and raised in Trinidad and Tobago, Moseley reflects upon the unique challenges and opportunities that drove him toward education and his life in Canada.

Richmond had given Moseley and his family opportunities to thrive in the world of athletics because the community was small and inclusive. Today, Moseley continues to coach, take care of his family, and play percussion from time to time.

Following this interview, Moseley was inducted into the 2018 Richmond Sports Wall of Fame for his years of dedication as a track coach.

What was life like growing up in Trinidad?

Many of the people around us weren’t fathers. There would be mothers with children but very few fathers. You may not know, but slavery was very, very rampant in the new world. The Spaniards tried to enslave the Carib Indians to work in the plantations, the sugar cane plantations, stuff like that. My mother had nine of us. I was smack in the middle. It was a struggle from that point of view.

A very funny thing happened when I was about nine or ten. My father worked for the Trinidad and Tobago Electricity Commission. Somehow they had discovered that he had high blood pressure and he was released from his job. Of course, we didn’t have any social services like welfare and stuff like that. With six children to support with no income, he got into some illegal activities and he was imprisoned for a while. My mother couldn’t go to the welfare office and say “well, my husband is in prison and I need to . . .”

How did you get into high school in Trinidad?

I decided to go up to the golf course and started caddying for a man who was the head of the Alcoa Steamship Company, a white Major Ed Collins. His wife also got interested in golf. The golf pro, who was black, asked me if I could come and pick up balls for her when she did her lessons, around nine or nine-thirty in the morning. He spoke to me one day and he said, “Mrs. Collins asked why you aren’t in school.” He told her my family was too poor to send me. We didn’t have free schooling. She was going to pay for me to go. The arrangement was that I would go to their house on Saturdays and help around the yard. This was a big break for me.

My mother went to thank this woman. Once again, a wonderful thing happened. She spoke to her husband, he spoke to his friend, and they arranged for my father to get a job. Things started to change. I was going to high school. I’d get home at just about four o’clock and take the next thirty-minutes and run to the golf course to caddy, so I could make some money to get to school the next day and cover my lunch.

What brought you to BC?

I got a job in the Civil Service [in Trinidad]. I worked in the Department of Education and Culture. There was a man up the road who worked in the Department of Education. Talking to him, I discovered he had some friends who were at university in Vancouver. I had read about Vancouver because of the Commonwealth Games in 1958. I got the idea, “I want to go to university.” I tried to get into the university in Trinidad, but there was a five-year wait, and, generally, you needed to have about eighty-five to ninety-five percent to get admitted. I didn’t want to wait that long, so, I got this friend to write one of his friends in Vancouver and ask them to send me a calendar. When the calendar came, I looked at it, and I applied to several places in Canada to go to university. I applied to McGill, University of Manitoba, and the University of BC. I wanted to come to Vancouver because I was told students are allowed to work at the university during the school year, and find employment during the off season. I thought, well, this is what I have to do.

What surprised you when you came to Canada?

One of the first things that surprised me was the restrictions on alcohol. I come from a society where I could walk into a liquor store, and I could buy a bottle of rum for my parents or somebody. On a holiday, my uncle would offer me a small drink of rum or something like that.

I was surprised that most of the people were white. There were very few black people around. The black people I met, they lived on the east side, and there were no black people that I knew, except people from the Caribbean.

Also, when I came to Vancouver you couldn’t go to a movie on a Sunday. In Trinidad, it was a big day for us to go to a movie on a Sunday.

How did you adjust to living in Vancouver?

I was extremely homesick because I came from a family where I had eight brothers and sisters. I had lots of friends around and I was working in the Civil Service.

When I came here, I didn’t know anybody. I’m at UBC and I met a guy from Jamaica. We roomed at the same place and after that I met some fellow Trinidadians and I hung out with them.

I had two groups of friends. A group associated with the steel band and another group into soccer.

You got your first teaching job in Kamloops. How did you return to do your master’s degree?

I had come down to a number of workshops in Richmond, in Vancouver, and I was particularly interested in counselling. I applied and the Kamloops School Board agreed to give me one of these sabbaticals. They paid seventy percent of my salary. I had three children. I applied to UBC. We settled in Richmond and I went to UBC. While I was there I was getting very good marks. My advisor, I was taking the course from him, he said “Why don’t you apply for the master’s [degree]? Change from the diploma to the masters. I was just amazed.

Things have worked out very, very well for me. This country has done amazing things for me. I don’t think I would have had as much success, and, to add to that, my children grew up here.

What moved you forward to seek education?

Having come from a very poor family I was fortunate to graduate from high school, which somebody paid for, and then when I was in the civil service I thought I wanted to get more education. Not being able to get admitted to the university in the West-Indies, and if I had been admitted I would have been able to go free, but I wanted to extend my knowledge. So when I came to Canada, it was to get a degree. I had hoped to go into medical school but I discovered a number of things. One, I don’t think I had the determination because if you’re going to be a doctor I think you have to have special skills. Also, I think I didn’t have the brains. I didn’t have the discipline, and I didn’t have the money [laughs]. Even when I finished my master’s degree, I was hoping to do a PhD but I had a wife and three children. A PhD was going to take three more years. Who was going to support my family in the meantime? My aim was to get as far as I could in education to make my life better than it was growing up in Trinidad and Tobago.

What was it like raising your family in Richmond?

My kids never faced a lot of discrimination and I would say I didn’t feel a lot of discrimination. On my soccer team, I had black kids, white kids, East Indian kids, Chinese kids. So I felt that Richmond was a very open community.

My kids were very involved in athletics. Had we lived in Vancouver we may not have had access as much, but in a smaller community like this there were lots of things available for us. My services were needed in coaching so I have been very, very comfortable here. If I go into the Steveston neighbourhood, I would encounter kids that I taught or kids who went to the schools where I was teaching. This is one of the things that I discover in many places that I go in Richmond.

Can you describe your experiences with coaching?

Well, I came from a background where we didn’t get any coaching. What I find here is, Richmond is a great area for kids in which to grow up because they’re exposed to so many things athletically. We have remained very, very involved in athletics. I coached at Lord Byng. I would start with cross country, then we would do volleyball, and then I would do basketball and then I would do track and field. When I moved to the secondary school, I did cross country. I also coached table tennis. I played table tennis for a while, and then I would coach track and field. I remained involved with the club since then coaching. I started coaching distance running because the first coach I worked with to learn was a distance coach. Then I took my training in sprints and hurdles. I have learned about that and I coach, also, long jump. I inherited a lot of information from my son, who was a very good long jumper and triple jumper.

What are your opinions and perspectives about women?

Having a daughter was very important to me to reinforce my beliefs. Women should be able to do anything that they want. So I think living with the family, you know, this sort of thing, having sisters reinforced the idea that, yeah, women need to be treated equally. So I would say, you know, the track team that I coached I have a lot of girls. The girls were also just as successful and that’s important to me. I think, as I said to you before, for most of our life we have not used women’s brains. The first woman I read about was Cleopatra, and then there was a woman named Boadicea who fought against the Romans. Recently, there was Gold Meir, Margaret Thatcher, and so on. I think the world would be a much better place if women were in charge.