oral histories

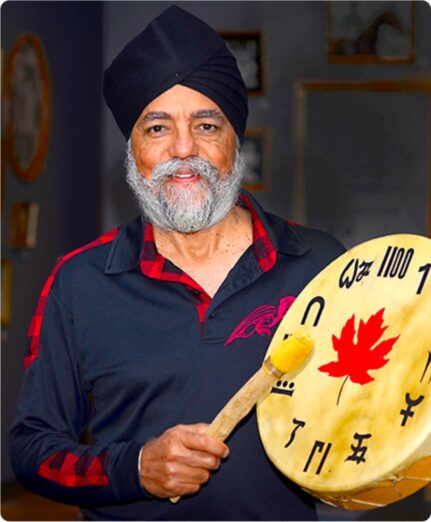

Kanwal Neel

The Canadian dream is not in making millions of dollars, but having a life where you are safe, you are happy, and you can continue to bring others in the fold.

In his far-ranging interview, internationally acclaimed educator Dr. Kanwal Neel shares memories of a childhood in Kenya, his family’s emigration to Canada, and his passion for his career as mathematics educator. Kanwal also shares his belief in contribution to community, volunteering and helping those not as fortunate.

Kanwal’s work won him honours over the years – the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for recognition of his significant contributions and achievements in 2012; Prime Minister’s National Award for Teaching Excellence in Science, Technology and Mathematics; and most recently an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree from the Kwantlen Polytechnic University for his commitment to the community in education, athletics and community service.

Tell us about your childhood in Kenya.

Growing up I was involved in athletics, in field hockey, in the Boy Scouts, and then, of course, our family would get a chance to travel. So the travel bug was with me also. It was really a life full of adventure, a life that took you to a variety of places, and also gave you an opportunity to reflect on who you are.

How would you describe your parents?

They are very adventurous. When they’d gone to South America, they travelled for a few months. They would book one night in wherever they’re flying and then find out where the locals stay. Then they go stay there for a month. Not even knowing the language, they would use sign language. That spirit of being able to accept what’s out there.

Why did your family come to Canada?

In the late ‘60s, Pierre Trudeau had started that whole idea of having immigrants here on a point system. So you could come with your family. Also there was a need for math and science teachers. Dad was a science teacher and I was finishing my O-levels, so Dad was figuring out what is the best option. We wanted to come as a family, so they felt it wasn’t okay to just send us to India or England or any of those things. As a family, we migrated to Canada.

What was your initial experience with Canadian society?

It was quite challenging going out. There was a lot of ignorance and racism, but at the same time, there were people who were very accepting and knowledgeable too. So you had the dichotomy. You had to kind of understand both sides.

You were involved in Bhangra, the Punjabi style of music and dance. How has awareness of it changed?

Bhangra has become quite mainstream and I’m so, so pleased when you see many performances which have become fusion art. I’ve seen performances where the Scottish Highland dancers and the Bhangra dancers perform together, or a First Nations drummer and the Dhol drum are playing together. This breaks barriers in many, many different ways.

How did you get involved with making math videos?

The Open Learning Agency at that time [1993] was wanting to make videotapes about teaching math. They had a number of people who could not graduate because they couldn’t get an equivalent of Math 11. So they needed a math course to graduate from high school – and these were adults who really were having a hard time. I go and audition and they said, “Teach us about the slope of a line.” All my math friends and geeks went in with their formulas and they were teaching the formulas. I was wearing shoes with shoestrings, so I took my shoelaces out and I showed them what slope was and how slope varied. The director says, “I finally get it. I don’t need formulas, I need something visual.” Long story short, they hired me as one of the co-hosts presenting it. There were two of us: I was the math person and my co-host was actually a stand-up comedian, Christina. We made sixteen half-hour shows and those shows were run by Knowledge Network for the next twenty years. That opened lots of doors for me.

What have you learned from your involvement with track and field?

I’ve had the privilege of officiating three Commonwealth Games, World Championships. Each one of these places you go, I’d probably would be the only person wearing a turban but by the same token, you see the profound acceptance of people when you are in the field of play, that all barriers get removed. You are feeling a sense of community, and many times, you see kids from poor nations who succeed because they put all of that behind. To them, sports is what matters.

Tell us about your thesis on numeracy in Haida Gwaii.

It was a fascinating time for me. A time to talk to carvers, jewellery makers, totem pole makers, talking to fishermen, talking to loggers, and hearing their stories. When you start talking to them, none of them said they used math, but when you get deeper into questioning them, they had profound knowledge of three dimensional spatial sense. They had profound knowledge of how do we have the sense of patterns, how do we understand the land, how do we understand the environment, how do we look at the whole notion of scaling, and how do we even go as simple as designing a button blanket. It came with the cultural stories, but then they embodied symmetry, they embodied looking at tessellations, they were all part of the ideas that were very, very intuitive for them. So, taking that intuitive sense and making it more concrete and making it more outward was the challenge.

The Komagata Maru incident involved the turning away of a steamship carrying passengers from India from Canada in 1914, which was part of racist immigration policies at the time. How were you involved with its commemoration?

1989 was the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Komagata Maru incident and I managed to work with one of the temples and did a number of events and have a plaque acknowledging it and had some events acknowledged in that event. The seed had been sewn into looking at the centennial in 2014 and then this year [2016] having the formal apology. So it’s been a long journey but it’s been a very fruitful journey. My goal in all of this was, just as an educator, how do we let others know about this Canadian incident and how do we make sure that we do not repeat such racism here?

How do you interpret the Canadian dream?

The Canadian dream is not in making millions of dollars, but having a life where you are safe, you are happy, and you can continue to bring others in the fold. When I look at every day in the news what happens in countries, even south of the border, I’m going, “Here we have a country which has a profound sense of not only accepting but being able to be with others who don’t have the opportunities.”