oral histories

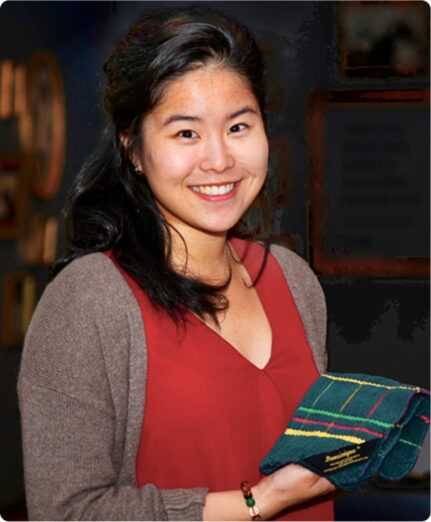

Dominique Bautista

I have been so integrated into Richmond, a community that has different layers of an Asian identity. That really reflects who I am at my core.

In her reflective interview, Dominique Bautista shares the story of her family’s arrival in Canada, growing up in Richmond, and her multiple identities as a Chinese-Filipino Canadian.

Inspired by her parents and grandparents, Dominique is now a young educator and highly engaged member of the community.

What is the story behind your name?

My full name is Mercedes Dominique De Joya Bautista, but I typically go by Dominique Bautista, just for ease. I was named after both my parents. My mom’s Mercedes and my dad’s Domingo. My middle name is De Joya, which isn’t a typical Western middle name. But in Filipino culture, it’s common for the children’s middle names to be their mother’s maiden name. Bautista is the product of my grandfather’s migration story. All my ancestral relatives on my father’s side were from a village in Fujian, in southern China. During the Communist outbreak, my grandfather and his father decided they didn’t want to stay. So they travelled across the South China Sea and ended up on the sandy shores of Manila. To assimilate, they decided they would change their last name. Our Chinese surname is Cai. My grandfather went to get it legally changed. The name of the judge presiding was Bautista, and my grandfather really liked it, so he decided he would ask for it. That’s how we got Bautista. Bautista is a Hispanic last name that reflects the colonial history between the Spaniards and the Philippines. With Bautista, my grandfather and our family would be able to get access to resources and services that you would if you were naturalized or if you were born a Filipino citizen — education, owning a home, businesses etc.

How did your family end up in Canada?

My dad left the Philippines on vacation with my grandfather one summer, and they came to Vancouver, and decided my dad and a few of his siblings would come to Vancouver to continue their high school and university education. My dad completed high school at Van Tech Secondary and then he went to UBC. My mom finished high school in Manila and then she did a couple years at the University of the Philippines there. She managed to badger my grandparents enough to let her go abroad, which was very unheard of at the time. She must have been really convincing. She ended up completing a degree at the University of San Francisco. She got her MBA as well. During that time, my dad and her kept in contact. Eventually, both of them ended up back in Manila for different family reasons. They rekindled their love and got married. They began their life there and had my brother in 1989. That was during the time of martial law. My dad decided they were going to move. The three of them hopped on a plane and came to Vancouver and left everything.

What brought your family to Richmond?

The first place they settled was in the core of downtown [Vancouver]. It was really busy and wasn’t the most conducive place to have a family, so they decided to move. They didn’t know too many people in Vancouver, so it was kind of scary. There were maybe one or two Chinese-Filipino families, but they heard Richmond was a really up and coming city. They decided on Richmond because my dad really loves Chinese food. Richmond was the place to go.

With the rest of your relatives in Asia, did you feel isolated?

Throughout university and undergrad and high school, I’ve always had a bit of an identity crisis, for someone who is born here, grew up here, but has really strong roots to Asia. At home, I spoke English and my parents spoke to me in Tagalog and Hokkien, which is a dialect that we speak in Fukien. I went to Mandarin school. I learned French for twelve years. Really ethnically charged, trying to make sense of that identity piece. Am I a Chinese Canadian? What does that mean? Am I Filipino-Chinese-Canadian?

What was it like to visit your grandparents in Manila, where your mother grew up?

When we would go visit, she would tell me stories about what it was like growing up there as a child. It was a really large house. They had an attic and they had a ballroom. They had a backyard with a swing set. They had large amounts of land because there were so many families coming and going. They also had a temple space upstairs. My grandfather’s aunt, my grand aunt, practices Buddhism. She’s a Buddhist monk basically and that was her area. It would be a really creepy space at night time, because it was severed off from the rest of the house. You’d have to go through this walkway and she had these curtains and it was very eerie. In the Philippines at night time, the crickets are chirping. It was really moist and everything is really musky and eerie. As a child, you’re always told, “Don’t bother your grand aunt. She’s doing her thing.” It was scary but, of course, as children, you’d still go anyway. My mom would do the same thing when she was my age, too.

How is food connected to your sense of identity?

I value my family, my conversations with my grandfather, value even the recipes, and the way that my mom cooks things and what she tells me as she cooks things like, “this ingredient comes from this place and you can only get it from here,” or “I remember cooking this in the kitchen with my own grandmother,” and, all these things that are unique to the moment. I have been so integrated into a community like Richmond, a community that has different layers of an Asian identity. That really reflects who I am at my core; someone still navigating what it means to be bi- or tri-culturally Asian, hyphenated, ethnically ambiguous, where people can’t tell if I’m Singaporean or Japanese.

You’re a teacher now. What was your family’s attitude toward education?

My dad was really encouraging of the humanities, which isn’t very typical for Asian families. He would always get me to read the newspaper and write about current events to hone my writing skills at a young age. My mom always brought me to the library. I was here all the time. So reading and writing was super, super important. I did Kumon [After School Math & Reading Program] as well because I needed to improve math. I was kind of your reverse Asian stereotype in terms of that.

How have your parents helped other Filipino immigrants?

They became points of contact for folks from Manila hoping to migrate here because they had been here so long, they were considered veterans. People would ask them, “What’s it like here? What’s the immigration process like? Who do we need to talk to?” because they had lived through it themselves.